The language people use can reveal a tremendous amount of insight into their preferences, beliefs, and attitudes. When we examine language use through quantitative or computational analysis, we can uncover patterns of behavior that are not discernable through evaluation of their content alone.

This article explores ways in which computational discourse analysis can help the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and the Intelligence Community (IC) better understand and monitor international political developments, crises, and threats, especially in nation-states or places where true preferences and strategies are difficult to observe. These include authoritarian regimes, violent extremist organizations, and other insular groups who display seemingly unpredictable behavior.

Specifically, quantitative analysis of syntax—the arrangement of words and phrases in speech or text—can provide information about group membership and perception of status in the international system [1], reveal how leaders and the political systems they represent conceptualize problems [2, 3], and indicate audience design, or how leaders may emulate or mirror the language of others [4]. Linguistic style matching is a phenomenon whereby speakers adopt—either consciously or unconsciously—the speaking styles of others in a shared space, such as the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) general debate [5]

Whereas to date the study of states and language in international relations has tended to focus on specific leaders and conditions [6–11], some research has taken a cross-national time series approach to understanding how language helps estimate policy positions in the world [12].

Studying syntactic and semantic patterns of language in the world can help national security and defense intelligence analysts understand and predict problems related to international events and crises, such as democratization and democratic backsliding [13], coalition formation and dissolution [14], and longevity of foreign leaders in political office [15].

Quantitative analysis of syntax can aid entities like the Defense Intelligence Agency in its annual worldwide threat assessment, which evaluates the military capabilities and political intents of nation-states and regional actors [16]. The discourse analysis techniques demonstrated below can help DoD and IC intelligence analysts foresee or anticipate political instability, explain changes in state governance or military capacity, and decode intentions behind bellicose rhetoric.

Language in the International System

Scholars of international relations already use annual, aggregate observational data to analyze and make predictions about global political dynamics—including gross domestic product per capita, governance, annual military expenditures, conflict involvement, trade volume, and population demographics. To this discussion, I add robust language data using text data from UNGA general debate sessions from 2004 to 2018 as a sample dataset (the techniques presented below are applicable to other datasets and corpora).

Some of the standard covariate indicators are dynamic and responsive to exogenous shocks, such as civil wars or interstate conflicts. Others, however, are slower moving and exhibit little variation over time—such as indicators of governance. For example, while some countries experience many internal changes in leadership and coalition dynamics, the level of governance may not change much, if at all, except in the cases of coup d’états [17].

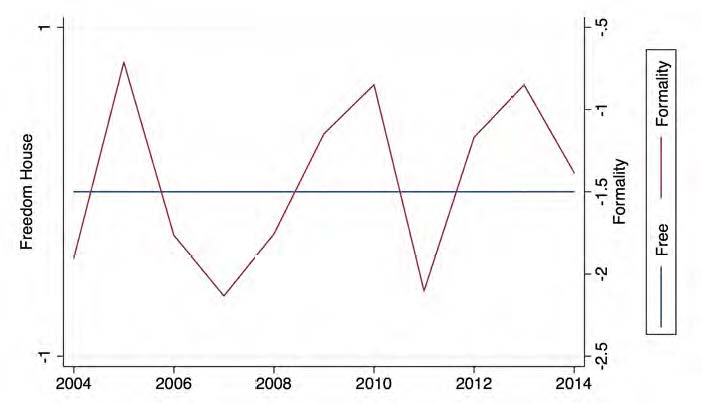

Figure 1 illustrates this point: the blue horizontal line shows that the United States has remained consistently classified as “free”, while the language used in the UNGA general debate has fluctuated over time, as shown by the red line on the second y-axis, which I will discuss in the next section.

Syntactic and Semantic Elements of Language

I examine five elements of language to demonstrate how they convey information about politics in the international system: syntactic simplicity, word concreteness, narrativity, deep cohesion, and referential cohesion [18]. Syntax simplicity describes how syntactically simple or complex a sentence, paragraph, document, or corpus is. This refers to the grammatical structure of the textbase, where more simple syntax is more easily understood and less cognitively demanding on the audience. On the other hand, complex grammar requires more cognitive effort to parse. Syntactic simplicity can indicate the relative status of a member of an organization, as complex syntax can mark hierarchy. For example, a junior member may use more complex language deferentially toward senior members as a sign of respect. Complex syntax can also identify in-group and out-group status.

Word concreteness measures tangibility and intangibility. Concrete words correspond to real-life referents (i.e., concrete nouns such as people, places, and things). Abstract words can be emotionally evocative, such as hope, fear, community, terrorism, support, or peace. Using abstract words can help an audience connect to broader themes, frame complex issues, and potentially build consensus without necessarily identifying specific details.

A narrative text tends to follow the traditional narrative, storytelling arc: introduction, rising action, climax, denouement, and resolution. Information presented in this format is easier to remember than expository (list-like) presentation as it helps the audience to contextualize the information within familiar heuristics. Expository language may instead present as a list or set of related concepts, relying on the audience’s working memory to sort the information.

Deep cohesion can be understood as global cohesion; in other words, the extent to which the entire body of information is broadly thematically related. Semantically and conceptually related ideas may thread throughout the textbase, but are presented in a more nuanced and complex format.

Referential cohesion, on the other hand, is more locally cohesive. Particular words, phrases, or ideas may be repeated in proximate sentences, or subsequent pronouns may refer back to antecedent concrete terms. Texts with high referential cohesion tend to be more quotable, memorable, or useful as soundbytes, whereas texts with deep cohesion often need to be summarized in order to be communicated succinctly.

These five syntactic and semantic aspects of language combine to form a composite feature called formality. Low levels of formality indicate familiarity, shared experiences and lexicon, and status parity. In short, people who use less formal language may view themselves as a part of a social system or community. High levels of formality may indicate that the speaker perceives himself or herself as an out-group member—showing deference to an in-group with higher status or hierarchy in the system.

How Democracies Speak

Regime type influences leaders’ use of formal language in three ways: through institutional constraints from the domestic bureaucracy and legislative branch, advisory oversight from the leader’s trusted inner circle, and accountability to both domestic and international audiences. Democratic regimes are defined by several political features, including meaningful competition for publicly held offices, an independent judiciary, and regular and fair elections [19–21]. These features serve to constrain democratic leaders in their daily activities, as well as in the international commitments they make, and the rules of the political system that influence democratic leaders’ freedom of speech. Legislatures and political advisors in open societies function as gatekeepers of policy change, vetting changes in foreign policy, tempering hasty and/or unilateral decisions, and encouraging consensus-building in the international community [22].

Democratic leaders also face more direct constraints from a trusted circle of advisors, confidants, and speechwriters. In democratic regimes, advisors should be less likely than in authoritarian regimes to blindly concur with leaders’ proposed policies. Rather, they are more likely to offer candid and contrary opinions about the leader’s foreign policy plans. Democratic leaders often solicit diverse opinions for policy speeches, which is especially useful given that they are accountable to a diverse constituency.

The role of audiences should also be considered when it comes to choices made by leaders. For example, democracies are likely to engage in consensus-building and diplomatic persuasion. In 2004, the Japanese delegation pronounced, “Peace and security, economic and social issues are increasingly intertwined. The response of the United Nations must be coordinated and comprehensive. UN agencies and organs must be effective and efficient [23].” Similarly, in 2012, the UK delegation declared: “The building blocks of democracy, fair economies and open societies are part of the solution, not part of the problem. And we in the United Nations must step up our efforts to support the people of these countries as they build their own democratic future [24].”

These features of democracies’ language are in part due to the influence of the national leader’s team of advisors and the extensive linguistic and ideological vetting that takes place before the speech is given. It is also partly due to the distribution of power between the branches of government; in other words, the leader generally does not make international claims, threats, or commitments without consulting and gaining approval from advisors and the legislature, and by extension, the general public, who can remove the leader from office for poor foreign policy performance.

Figure 1. Variation in language and governance over time (Country: USA)

Language in Non-democracies

Leaders from non-democratic countries generally face different and often fewer constraints than democratic leaders. Government types and governance can be compared in different ways and along varying schema, including the Polity IV scale [17], the Freedom House typology [25], and varying approaches to classifying types of non-democracies [26–29]. I map linguistic features onto institutional features to provide a context for interpreting language in the international system. The depth and robustness of public institutions characterizes the level of formality in public venues; of the non-democratic regimes, party-based ones have the most bureaucratic accountability, with personalist regimes having among the least [19, 26, 28, 30].

These institutional features are also used to explain other political phenomena, like compliance with international treaties and participation in conflict. Using the typology set out by Lai & Slater [28], political scientist Olga Chyzh evaluates authoritarian regimes’ patterns of signing and complying with international treaties [31]. Of personalist regimes, Chyzh writes, “…personalist leaders are effectively not constrained (or almost so) by the need to seek approval on all except for very particular policy issues [31].”

Thus, in personalist and monarchical regimes, increased formality could be more easily attributed to specific individuals’ contributions and should have language patterns least similar to democracies. In particular, leaders of authoritarian regimes tend to use distinctive linguistic approaches in their public addresses, including honorifics and more abstract and deferential language. We can see this in the words used in 2009 by the Ethiopian representative:

“Mr. President, It is indeed a great pleasure for me to extend my warmest congratulations to you on your election to preside over this 64th Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations. Permit me also to express my appreciation to the outgoing President for his effective leadership during the course of the last Session of the General Assembly [32].”

The 2004 speech by the Venezuelan representative illustrates the abstractness, referential cohesion, and tone in some authoritarian language (highlighted in bold):

“There are moments we can describe as historical turning points, when nations and peoples must decide where they stand. This is one of these moments, when history will judge us as leaders, and examine if we were democratic leaders that represented the will of our peoples. It is clear that the people of the world are taking a stand, against neoliberal economics and war. They are fighting against those who would impose their will by military and economic force [33].”

Notably, some authoritarian regimes, like party-based political systems, can display quasi-democratic traits that may make them more likely to speak and behave in a public forum like democracies. Chyzh provides further useful insight into how these regimes are constrained, writing that, “In contrast, authoritarian leaders with larger domestic bases— oligarchic dictators—face decision-making constraints in more policy areas, as larger domestic bases have more diverse interests.

In addition, domestic institutions, such as cabinets, juntas or politburos, common to oligarchic regimes, tend to induce a status-quo bias, making policy change, such as entering into an international agreement, more difficult [31].” For example, the Chinese single-party political system has pseudo-democratic practices, such as elections and party member incentives for loyalty and participation.

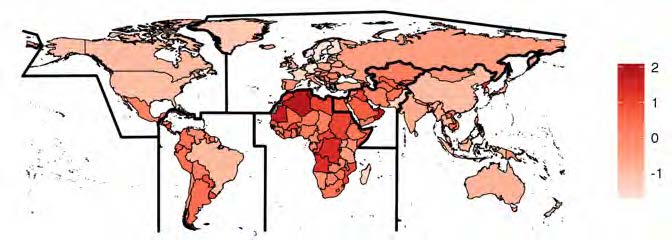

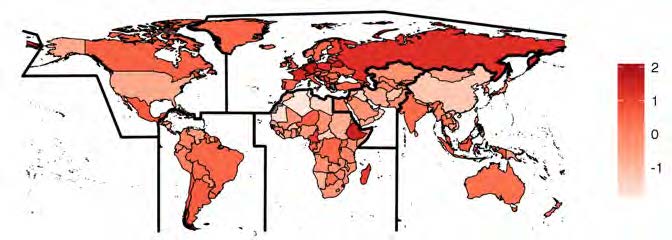

Figure 2. Syntactic Complexity in the World

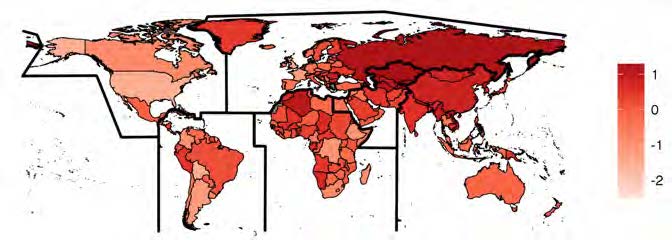

Figure 3. Word Abstractness in the World

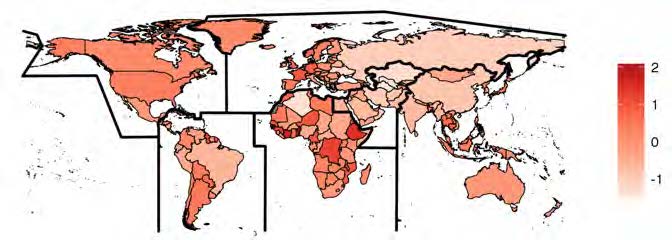

Figure 4. Expository Language in the World

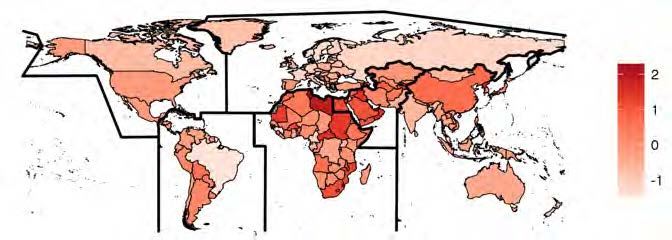

Figure 5. Deep Cohesion in the World

Figure 6. Referential Cohesion in the World

Data, Methods, and Results

To explore the relationship between governance and language, I use text data from the UNGA general debate between 2004– 2018, analyzed with Coh-Metrix software [18, 34]. Coh-Metrix is a computational linguistics tool used to analyze syntactic and semantic properties of natural language. At present, Coh-Metrix only operates on Englishlanguage corpora; however, an updated version called Coh-MetrixML will analyze syntax and semantics in five other languages: French, Spanish, German, Arabic, and Chinese. Linguistic features derived from Coh-Metrix include passive voice, latent semantic analysis, left-embeddedness, and age of lexical acquisition. Coh-Metrix and Coh-MetrixML analyze documents across more than 100 indices, and a principle components analysis reduces the language features to five dimensions: syntax simplicity; word concreteness; narrativity; deep cohesion; and referential cohesion. I discuss these features in more detail below.

The dependent variable from the empirical model comes from the Freedom House qualitative measurement of political rights and civil liberties, and categorizes countries as Free (0), Partly Free (1), and Not Free (2).

Figures 2 through 6 show maps of the five categories of syntax and semantics in the world, divided by DoD Geographic Combatant Commands. In Figure 2, we observe more complex syntax in countries with darker red color. In Figure 3, countries with darker shades of red use more abstract language, while those shaded lighter use more concrete terms. Figure 4 shows countries that use more list-like or enumerative language to convey their messages shaded in darker red, while those whose words follow the narrative arc” more closely are shaded lighter. Figures 5 and 6 show deep and referential cohesion, respectively.

Countries whose language has more overall, or global, cohesion tend to speak along broader thematic tropes, whereas those with higher referential cohesion tend to be more locally repetitive in their concepts. We can observe clear differences between regions, governance types, and levels of development in these patterns.

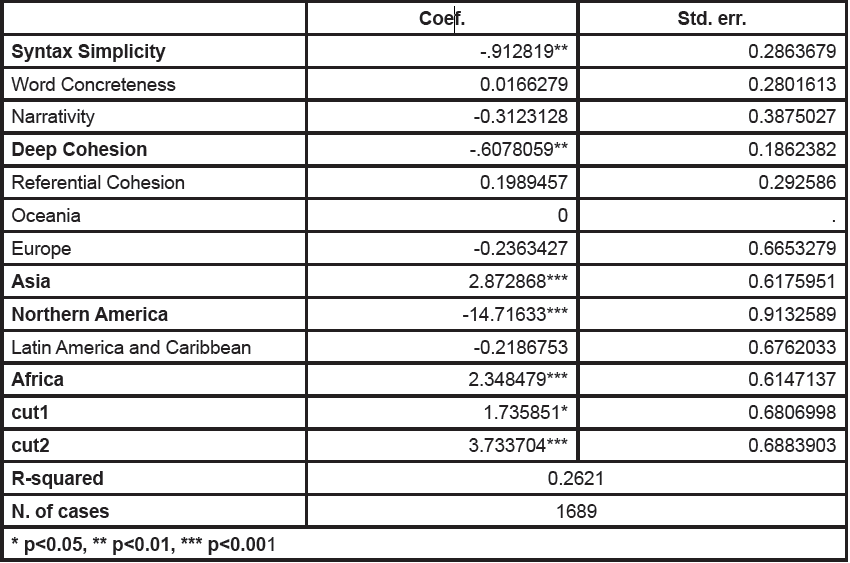

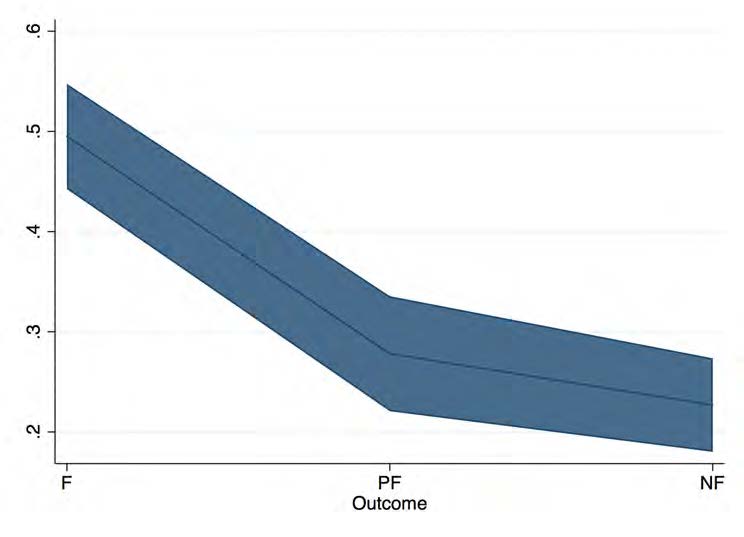

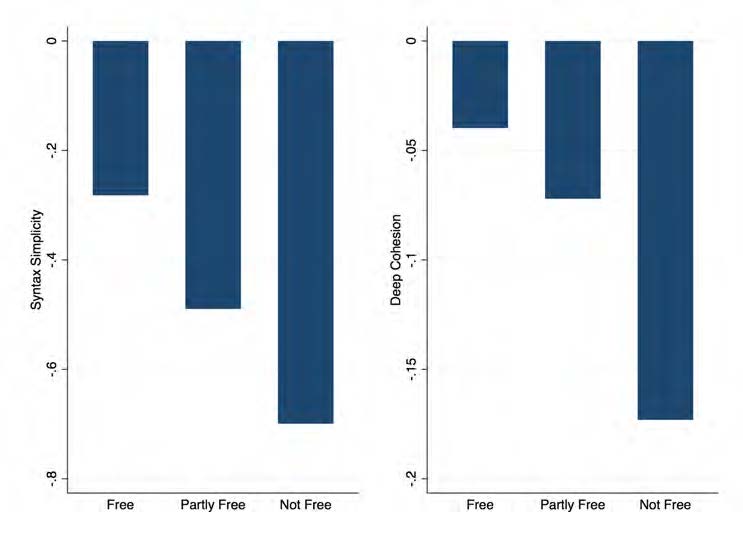

Table 1 shows the results of a generalized linear model with an ordered logit estimator, using Stata 15 software. Figure 7 shows the marginal effects of the covariates on the dependent variable, holding all covariates at their means. Countries that are more free use simpler syntax, whereas those that are less free tend to use more complex syntax. Similarly, countries that are rated more free tend to have higher levels of deep cohesion, and less free countries have less deep cohesion in their language.

This can be interpreted as follows: simpler syntax and deeper cohesion tend to suggest that there is a great deal of shared meaning and familiarity among countries using these language styles. On the other hand, countries that are highly repetitive and use more complex syntax may be trying to project or convey their authoritativeness, stature, or accomplish greater legitimacy in the international system by using more formal language styles. Extant research has established that individuals with genuine authority and power need not leverage their language to overcome perceptions about their legitimacy. Similarly, individuals who are members of an in-group tend to use more simple language, and in this way both syntax and semantics can provide clues to which members in the international system perceive themselves as members of the in-group, or the out-group.

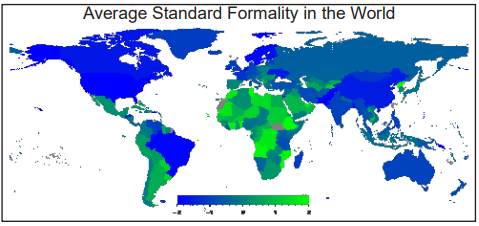

Figure 8 shows syntax and semantics patterns by country type in the world according to the Freedom House Freedom in the World ratings. More free countries use simpler syntax and have higher levels of deep (or global) cohesion than do partly free or not free countries. Figure 9 represents these relationships geographically: darker blue indicates informal language, while greener colors indicate more formal language.

Table 1. Principle Components and Level of Freedom in the World

Figure 7. Marginal Effects of Syntax and Semantics on Level of Freedom (from Table 1)

Figure 7. Marginal Effects of Syntax and Semantics on Level of Freedom (from Table 1)

Figure 8. Syntax Simplicity and Deep Cohesion in the World

Figure 8. Syntax Simplicity and Deep Cohesion in the World

Other Applications

Studying syntax and semantics can help DoD and the IC better understand the consequences of online media influence over political events, such as elections and candidate behavior; the rise of new regional threats; the emergence and dissolution of allegiances and alliances between states and actors; and counterintelligence insight using words to infer latent qualities like status, hierarchy, and personality.

Analyzing the content and the style of language can help us make sense of complex “hard security” issues like nuclear aspirations and antagonism in North Korea, the effects of populist language on impressionable constituencies, the stability of authoritarian regimes and longevity of leaders, and the spread of terrorist propaganda for recruiting new participants. It can also enlighten us about “soft security” issues in the realm of human security, such as the spread of infectious diseases, the mobilization of radical domestic terrorist groups, and the effects of climate change on vulnerable and mobile populations.

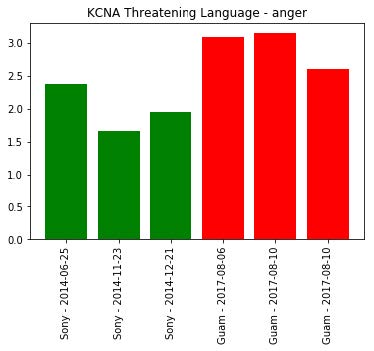

North Korean state media (KCNA) is another potentially valuable source of information about internal regime dynamics. Figure 10 shows differences in the amount of anger conveyed in articles about the Sony hack in 2014, and regarding potential military action against Guam. Interestingly, the level of anger was lower in the 2014 context where North Korea carried out their threat than in 2017 when the regime made threats against Guam. One possible interpretation of this could be that in contexts where an actor intends to follow through on the threat, less anger is conveyed as it is being “held in reserve” for carrying out the actual threat. On the other hand, in cases where a leader or regime is blustering or bluffing, they convey more anger as there is no immediate intent to follow through on the threats.

Figure 9. Average Standard Formality in the World

Figure 10. Threatening language in North Korean sate media

Future Directions

Computational discourse analysis may also aid DoD in its efforts to develop automated technologies for the extraction of useful information from very large datasets for defense analysis. For example, in 2012, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) began work on a project called Deep Exploration and Filtering of Text (DEFT), which seeks to develop a deep natural-language processing architecture for text and audio analysis. According to DARPA, DEFT’s purpose is to “find and represent key information, including information on entities, relations, events, sentiment, beliefs, and intentions” from multiple streams of data [35]. Developing a truly automated solution will require additional steps to move from data extraction to intelligence production, and computational discourse analysis can play a critical role in identifying key patterns in behavior, with human analysts playing central roles in interpreting results from computer-aided analysis [36]. Individual analysts remain the most important part of the analytical process. While computers excel at sorting and categorizing information, humans have the unique ability to contextualize, interpret, and communicate that information.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Minerva Initiative (DoD) Award #FA9550-14-1-0308.

References

1. Kacewicz, E., Pennebaker, J. W., Davis, M., Jeon, M., & Graesser, A. C. (2010). The language of status hierarchies. Manuscript Submitted for Publication.

2. Levelt, W. J. (1999). Producing spoken language: A blueprint of the speaker. In The neurocognition of language (pp. 83–122). Oxford University Press.

3. Lupyan, G. (2016). The centrality of language in human cognition. Language Learning, 66(3), 516–553.

4. Bell, A. (1984). Language style as audience design. Language in Society, 13(2), 145–204.

5. Niederhoffer, K. G., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2002). Linguistic Style Matching in Social Interaction. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 21(4), 337–360. https://doi. org/10.1177/026192702237953

6. Blaydes, L. (2013). Compliance and resistance in Iraq under Saddam Hussein: Evidence from the files of the Ba ‘th Party. In AALIMS Comparative Politics Workshop.

7. Bligh, M. C., Kohles, J. C., & Meindl, J. R. (2004b). Charting the language of leadership: a methodological investigation of President Bush and the crisis of 9/11. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3), 562–574. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021- 9010.89.3.562

8. Dyson, S. B. (2006). Personality and foreign policy: Tony Blair’s Iraq decisions. Foreign Policy Analysis, 2(3), 289–306.

9. Fariss, C. J., Linder, F. J., Jones, Z. M., Crabtree, C. D., Biek, M. A., Ross, A.-S. M., … Tsai, M. (2015). Human rights texts: converting human rights primary source documents into data. PloS One, 10(9), e0138935.

10. Klebanov, B. B., Diermeier, D., & Beigman, E. (2008). Lexical Cohesion Analysis of Political Speech. Political Analysis, 16(4), 447–463.

11. Winter, D. G., Hermann, M. G., Weintraub, W., & Walker, S. G. (1991). The personalities of Bush and Gorbachev measured at a distance: Procedures, portraits, and policy. Political Psychology, 215–245.

12. Baturo, A., Dasandi, N., & Mikhaylov, S. J. (2017). Understanding state preferences with text as data: introducing the UN General Debate Corpus. Research & Politics, 4(2), 2053168017712821.

13. Boix, C., & Stokes, S. C. (2003). Endogenous Democratization. World Politics, 55(4), 517–549.

14. Bailey, M. A., Strezhnev, A., & Voeten, E. (2017). Estimating dynamic state preferences from United Nations voting data. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(2), 430–456.

15. Windsor, L., Dowell, N., Windsor, A., & Kaltner, J. (2017). Leader Language and Political Survival Strategies. International Interactions, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2017.1345737

16. Ashley, R. (2018, March 6). Statement for the record: Worldwide Threat Assessment. Defense Intelligence Agency. Retrieved from https://www.dia.mil/News/ Speeches-and-Testimonies/Article-View/Article/1457815/statement-for-the-recordworldwide-threat-assessment/

17. Marshall, M. G., Jaggers, K., & Gurr, T. R. (2006). “Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800– 2009.” URL: http://systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm

18. McNamara, D. S., Graesser, A. C., McCarthy, P. M., & Cai, Z. (2014). Automated evaluation of text and discourse with Coh-Metrix. Cambridge University Press.

19. Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2010). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143(1–2), 67–101.

20. Levitsky, S., & Way, L. (2002). The rise of competitive authoritarianism. Journal of Democracy, 13(2), 51–65.

21. Przeworski, A. (1991). Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America. Cambridge University Press.

22. Bligh, M. C., Kohles, J. C., & Meindl, J. R. (2004a). Charisma under crisis: Presidential leadership, rhetoric, and media responses before and after the September 11th terrorist attacks. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(2), 211–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.02.005

23. Koizumi, J. (2004, September 21). A new United Nations for the new era. Statement by the Permanent Mission of Japan to the UN at the Fifty-Ninth Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.un.emb-japan.go.jp/statements/koizumi040921.html

24. Cameron, D. (2014, September 24). Statement by the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom before the General Assembly of the United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/ga/69/meetings/gadebate/24sep/uk.shtml

25. Freedom House. (2006). Methodology: Freedom in the World 2006. Retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world-2006/methodology

26. Geddes, B., Wright, J., & Frantz, E. (2014). Autocratic breakdown and regime transitions: A new data set. Perspectives on Politics, 12(02), 313–331.

27. Goemans, H. E., Gleditsch, K. S., & Chiozza, G. (2009). Introducing Archigos: A Dataset of Political Leaders. Journal of Peace Research, 46(2), 269–283. https://doi. org/10.1177/0022343308100719

28. Lai, B., & Slater, D. (2006). Institutions of the offensive: Domestic sources of dispute initiation in authoritarian regimes, 1950–1992. American Journal of Political Science, 50(1), 113–126.

29. Weeks, J. L. (2012). Strongmen and Straw Men: Authoritarian Regimes and the Initiation of International Conflict. American Political Science Review, 106(02), 326–347. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055412000111

30. Slater, D. (2003). Iron cage in an iron fist: authoritarian institutions and the personalization of power in Malaysia. Comparative Politics, 81–101.

31. Chyzh, O. (2014). Can you trust a dictator: A strategic model of authoritarian regimes’ signing and compliance with international treaties. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 31(1), 3–27.

32. Mesfin, S. (2009, September 26). Statement by the Minister for Foreign Affairs of Ethiopia before the General Assembly of the United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/ga/64/generaldebate/ET.shtml

33. Pérez, J. A. (2004, September 24). Statement by the Venezuelan Ambassador before the General Assembly of the United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/webcast/ga/59/statements/venspa040924.pdf

34. Windsor, L., & Cai, Z. (2018). Coh-Metrix-ML (CMX-ML). Minerva Initiative FA9550-14-1- 0308.

35. Onyshkevych, B. (2014, December). KB representation of text, audio, images, and video. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Retrieved from http://www.akbc.ws/2014/slides/onyshkevych-nips-akbc.pdf

36. Onyshkevych, B. (n.d.). Deep exploration and filtering of text (DEFT). Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Retrieved from https://www.darpa.mil/program/deep-exploration-and-filtering-of-text